Carhartt-less Behavior

When clothes lose their ability to signal social status, the only way forward is virtue signaling.

There’s this running gag about hipsters and their love of workwear. The brand Carhartt is especially valorized among this set. The idea is simple: hipsters are usually well-off people by way of their parents’ trust funds, but pretend to be poor as they believe that being a “real artist” is being poor. Cue them buying as much workwear as possible as they romanticize the idea of being a blue-collar man at a manufacturing plant while simultaneously looking down on actual trade work.

I live in Brooklyn, the hipster capital of the East Coast.1 Speaking of capital, that’s something most hipsters have. I mean this in both an economic and social sense. The average hipster is flush with economic capital from their hedge-fund-managing parents, and flush with social capital from their low-paid-but-high-prestige job as a tastemaker at Pitchfork or some other cultural publication I don’t even know about because it’s too “underground”.

Now, I may live in Brooklyn, and I am a writer, but I am not a writer in Brooklyn. I am aware that being a “writer in Brooklyn” has certain cultural connotations. Most writers in Brooklyn are transplants. If you’ve ever watched Lena Dunham’s HBO show Girls, about four twenty-something bohemian-type transplants in Brooklyn, you’ll know exactly what I’m talking about. And even when a “writer in Brooklyn” is not a transplant, they typically come from one of the affluent areas of Brooklyn: Park Slope, Williamsburg (minus the Hasidic side), and Cobble Hill.

Instead, I live in the working-class immigrant neighborhood of Sunset Park. I’ve rarely seen anyone walking around my neighborhood wearing Carhartt. Many instead wear workwear that is even cheaper, as Carhartt is one of the costliest workwear brands (and well worth the asking price to be used for manual labor). Much like how it is normal for a professional photographer to spend $3000 on a new lens but seen as a splurge to a photography hobbyist, the fact that Carhartt is a costly workwear brand reinforces its value as a status symbol to hipsters. Working-class people who recognize the high quality of Carhartt pay its prices out of necessity, so it isn’t seen as a splurge, while hipsters pay Carhartt’s high prices to look cool.

When I take the subway (the L train, usually) to one of those hipster neighborhoods, that’s when that orange Carhartt logo starts menacing me everywhere I go. You’d think those hipsters would have an aversion to orange after they spent four years raging at a certain politician.

When I saw an article just published in The Nation2 titled “You Can’t Even Tell Who’s Rich Anymore”, I knew it was going to be about clothing. In the article, the author (a professional architectural and cultural critic) bemoans the fact that rich people no longer dress like what we think rich people should dress like:

If I had as much money as a Zuckerberg or an Arnault, I would leave the house every single day in impeccable and expensive outfits. I would rock vintage Chanel and wear long gloves and big sunglasses and the weird statement jewelry they sell at art museums. I would own Miu Miu shoes. I would have a personal tailor and a closet the size of my living room.

You used to be able to look at someone and tell that they were rich. Clothes have always been an important class signifier. The magnates of old all had personal tailors, custom suits, beautiful shoes, and exquisite yet curated jewelry. A child asked to stereotype a rich person will tell you they wear a fancy suit or a ballgown with a pearl necklace. But even when I was a child, the richest people in the world no longer dressed like that. Formality has long been equated with wealth, but wealthy people, off the red carpet, no longer embrace formality. What a waste!

What is lost when sartorial symbols of labor—be they working-class-coded such as Carhartt and Dickies or the technical gear necessary for doing certain jobs or activities—are appropriated by rich people? You might be thinking, “But, Kate, doesn’t this signal that we will soon be dressing in a newly aesthetically classless society?” Haha, no! That’s what I find most interesting about all of this: If we look beneath the surface of high fashion, the added insult to injury (beyond Tiffany’s selling NFT bling) is that the rich’s appropriation of “ugliness,” “normalcy,” and working-class aesthetics is inherently ironic because they are rich and sometimes, in the case of such trends as over-articulated ugly dad shoes, that irony is explicit.

First of all, perhaps the author doesn’t realize that the fact that rich people don’t spend their money splurging on designer clothing is how they got rich in the first place. Indeed, rich people (especially in tech) have developed such a reputation for dressing plainly that looking unkempt is now a heuristic for technological brilliance.

And second of all, not every workwear enthusiast with callus-free hands is actually some hipster trying to be ironic.

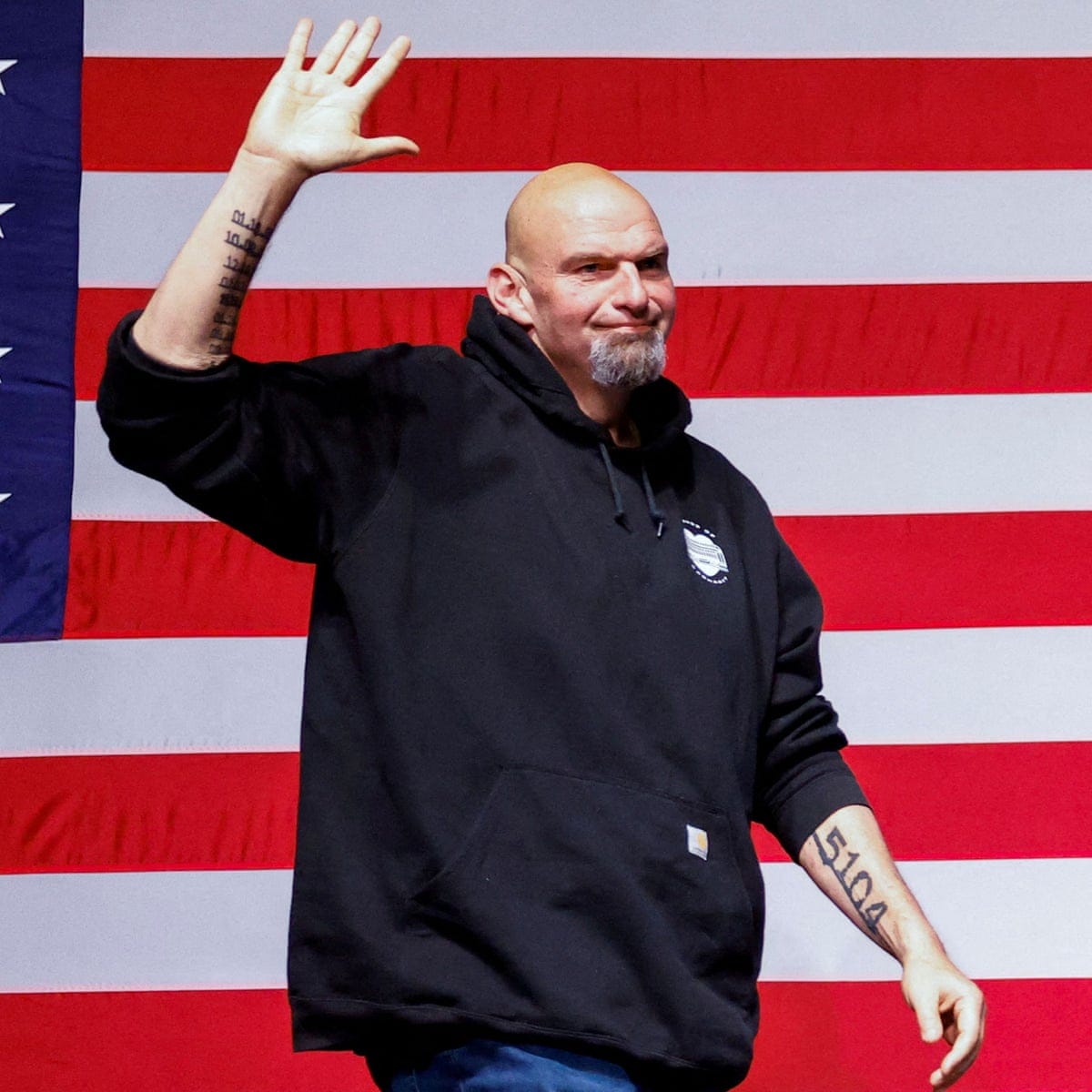

Take, for example, Pennsylvania senator John Fetterman. I’ve written about him before in regards to his race with celebrity TV doctor Mehmet Oz. I saw many photos of Fetterman in Carhartt, and I remember looking him up on Wikipedia and finding out that he grew up well-off, that his father was a partner at an insurance firm that Fetterman was supposed to take over, and that he had a Master’s degree from Harvard paid for by his wealthy family. In short, he was exactly the kind of guy that would wear Carhartt hoodies.

There were a lot of accusations of inauthenticity during the 2022 Pennsylvania Senate race. Oz had the accusation of being a snake-oil salesman that made questionable supplements fly off nutritional store shelves. And Fetterman had the accusation of pretending to be working-class by wearing Carhartt.

But how do we know for sure that Fetterman was only wearing the hoodies to try and pretend to be working-class? I just spent a lot of time talking about how hipsters have appropriated the Carhartt aesthetic. Considering that the concept of Carhartt is now associated with people that have never worked manual labor in their life, it’s impossible to say if he was pandering or not. Perhaps he just likes how the clothes look.

But there is another major takeaway from his Carhartt discourse. As affluent people have moved on from displaying their status via conspicuous consumption, they now display status through other means. The status signaling value of designer items has decreased a lot with this shift. Wearing clothing or carrying bags with designer logos is now considered be tacky: a sign of gauche nouveau riche mentality, or even a sign of poverty. And the symbols that once signified one's status as a manual laborer, like Carhartt or Dickies, are now worn by trust-fund kids across the world.

Some people lament that one cannot tell who is rich anymore. I disagree. Sure, it’s now harder to judge by the clothes one wears. But you can still tell by the way one talks and the views one holds.

A common theme in my work has always been that certain beliefs are held by certain people, and that whether or not one espouses those beliefs can reveal their socioeconomic position.

In my earliest essay on this Substack, I discussed how affluent Asians often hold a different set of values from poor Asians. I expanded on this for an article I wrote for Tablet. The wealth gap between the top 10% of Asian Americans and the bottom 10% is the highest gap for any race in America. Asian Americans seem to come in two stereotypes: the affluent doctor and the poor restaurant delivery driver.

In Jay Caspian Kang’s book The Loneliest Americans, he discusses how

Before the “Chinese virus,” I’d always come across assimilated Asian men venting on social media about the time one of their white neighbors in buildings just like mine mistook them for deliverymen, which was always followed up by a firm statement of their credentials, something like, “I guess he didn’t know I am a journalist/doctor/lawyer/hedge fund manager!” It’s embarrassing for both sides when this happens, but the implication has always felt so bizarre to me—the real offense is being mistaken for being poor. Every immigrant group engages in these sorts of differentiations. But what sets modern, assimilated Asian Americans apart is that our bonds with our “brothers and sisters” are mostly superficial markers of identity, whether rituals around boba tea, recipes, or support for ethnic studies programs and the like.

Many affluent people are scared of being seen as poor. But wearing the right clothes is no longer a symbol of wealth. People now have to show their status in other ways. For the affluent Asian, this usually involves expressing support for policies that actively harm poor Asians. One may wonder how any Asian could support affirmative action when it is literally institutional anti-Asian racism. But consider the fact that affluent Asians know the right things to say and the right extracurriculars to participate in to get into good colleges, while the poor Asian has no choice but to brute-force their way in by getting their kids into a top public school and then score as high as possible on the SAT. The affluent Asian can afford to support affirmative action, which earns them brownie points from their fellow liberal elites, while pulling the ladder from poor Asians.

Generally speaking, if someone supports something that seems to negatively impact them, then that person is showing off the fact that they can self-criticize and not be harmed by its effects. Have you ever heard of Race2Dinner?

The concept is simple. Eight to ten White women pay a total of $2,500 to have a two-hour dinner with “antiracist” activists Saira Rao and Regina Jackson. During this dinner, they are told about why being White is bad and read excerpts from Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility.

Now, you may think, who would pay good money to go to a dinner where you are criticized for two hours straight? Not poor White people. This act of ritual self-flagellation is meant to signal the high socioeconomic status of the White women who attend, because only rich people could and would pay for such an event. It is also a signal of being “with the times” or on trend, as “antiracism” programs are all the rage these days. I don’t think a poor White person living in an opioid-ravaged Appalachian town cares much for the sneering elitism of Robin DiAngelo’s work, nor being seen as trendy by participating in “antiracism” classes, as their primary concern is putting food on the table.

It’s no surprise then to learn that progressive activists, a group that most hipsters would fall under, and the group that is now colloquially called woke, are composed of some of the wealthiest people in America:

[P]rogressive activists are much more likely to be rich, highly educated—and white. They are nearly twice as likely as the average to make more than $100,000 a year. They are nearly three times as likely to have a postgraduate degree. And while 12 percent of the overall sample in the study is African American, only 3 percent of progressive activists are. With the exception of the small tribe of devoted conservatives, progressive activists are the most racially homogeneous group in the country.

I don’t doubt the sincerity of the affluent and highly educated people who call others out if they use “problematic” terms or perpetrate an act of “cultural appropriation.” But what the vast majority of Americans seem to see—at least according to the research conducted for “Hidden Tribes”—is not so much genuine concern for social justice as the preening display of cultural superiority.

Many people have also wondered why affluent Latinos keep using the word Latinx when it is clearly unpopular among the overwhelming majority of Latinos. But its unpopularity is its selling point. If Latinx was a popular term, it would no longer hold elite status. By using a word so garish and offensive to the average Latino, elite Latinos are able to signal their status by just changing a single syllable.

Many views woke people espouse are only accepted by a small number of people, as shown in the widely-criticized NPR tweet below claiming there is “limited scientific evidence” for sex differences in sports. Again, the unpopularity ends up proving their elite status, as they can imagine that everyone else is stupid for not being as “enlightened” as them.

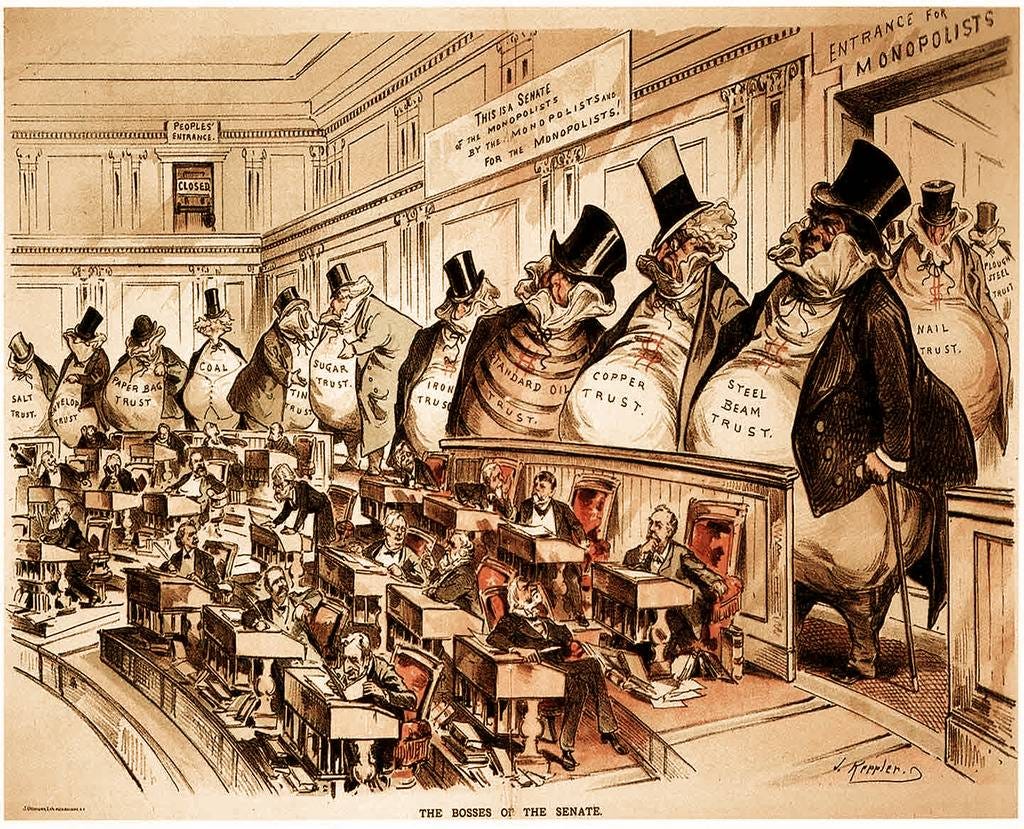

As outward markers of social status such as clothing have now become unreliable indicators of class, expect virtue signaling to rise even further. Perhaps we should go back to the days when rich people were obviously rich just by looking at them. At least then they wouldn’t have to virtue signal all these policies that actively harm poor people.

Bring back robber baron outfits.

The other regional hipster capitals include Portland on the West Coast, Austin in the South, and Minneapolis up north. Connect them and they form a sort of hipster baseball diamond.

You may be wondering why someone like me would read the wokest legacy news publication out there. I read The Nation very often. For me, there’s a certain charm to reading the opinions of those you may not agree with. You know how some people watch NASCAR hoping to see collisions? That’s the way I read political commentary. Sometimes people want to watch cars glide gracefully around the track, sometimes people want to watch cars crash and burn.

![MEME] @workwearheads : r/streetwear MEME] @workwearheads : r/streetwear](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!MHSh!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F24538b0d-76fd-44b8-8bc2-9a6ae4807f3c_750x747.jpeg)

Stolen valor-

I had a boyfriend in Portland, Oregon back in 2010 who got a bunch of Indian casino money each month. He desperately wanted to think of himself as working class.

I did not have any such money and stood for 8 hour shifts in high heels doing people's makeup (back when MAC 'strongly encouraged' high heels).

Anyway, the man went out of his way to buy a vintage Toyota, all the very, very best 'working gear' (his job was doing cocaine in the middle of the day and watching pornography) and of course, Carhartt boots. His justification for all this was

'it'll last a lifetime. I'm not fancy. Unlike you, I'm not superficial.'

The effort this man went to to pretend he was poor was way more work than actually being poor.

Anyway, nothing bad ever happened to him because every wrong turn he ever made was cushioned by money. But he sure was insufferable.

A colleague who saw me with Howard Zinn's History of America asked me why I was reading it and I replied so I could know what the enemy was thinking. Which is also why I, too, subscribe to and read The Nation. Always worth a laugh, I hasten to add their writers are not really the enemy, but misguided souls, good writers usually, and have the knack for getting their work into print. I just wish they'd bring someone with the point of view and wit of Christopher Hitchens back.