The Irony of Immigrants Valorizing Higher Education

Immigrant parents send their kids to college for a better future. But it doesn't go the way they expect.

Last week, I wrote The Irony of American Assimilation, where I challenged common beliefs about what assimilation is.

Let’s expand on that idea and think about the process of immigration and assimilation. The United States has long been a shining city on a hill; a place for the poor huddled masses yearning to breathe free. This country, which isn’t even 250 years old yet, has been through quite a lot, to say the least. We fought a bloody revolution to split from King George. We fought an even bloodier Civil War to reunite North and South. All the while, we accepted waves upon waves of new immigrants.

And what do immigrants do? Immigrants try to assimilate.

I live in a neighborhood of immigrants. These immigrants work hard so that the next generation doesn’t have to make the sacrifices they did. Their children will never have to experience the struggles of learning English or hear native-born Americans snickering at thick accents and imported customs. Many immigrants are shocked that America enshrines free speech as a core pillar of our national identity, especially those from authoritarian regimes where free speech only exists for the people who parrot the ruling regime’s propaganda.

And many immigrant parents really want the best for the next generation. The most obvious path to upward mobility is via higher education. The more elite the college, the better the chances of professional success. Immigrants want their kids to get into the best schools possible, as they can’t really envision another path forward. That’s why Asian immigrant parents will come out in full force to protect their kids’ educational prospects.

But what happens to their children? Their kids don’t really understand how hard it was for their parents to help them succeed. Immigrant parents instill values of hard work and education onto their progeny. The parents tell the children that being educated is the best guarantee of upward mobility.

So when their kids actually go to the schools their parents tell them are the best, they adopt the values of the people around them. After all, it was their own parents that told them these schools were superior.

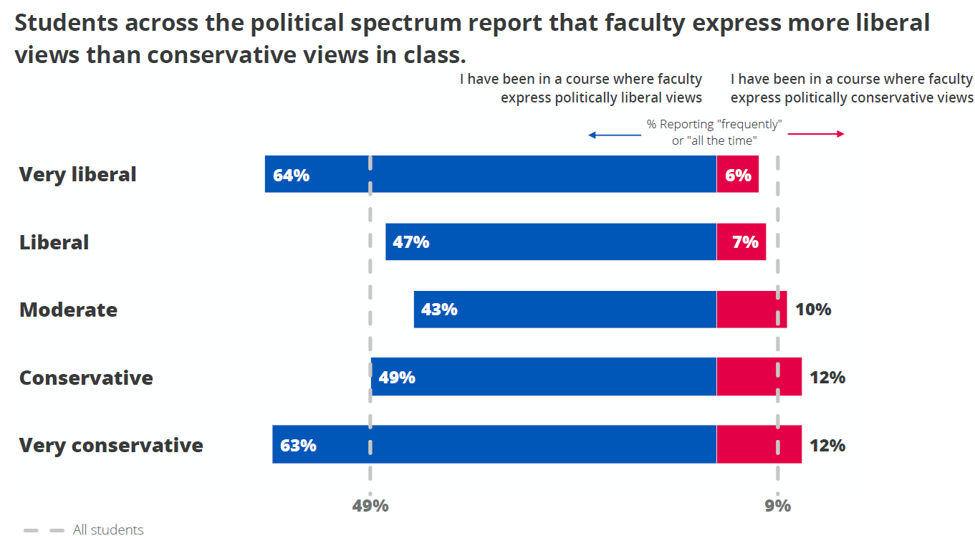

And what do America’s academies of higher education teach these days? I mean, we all know how the professors lean.

So we have parents that tell their kids that these professors are the best and brightest and higher education is the best way forward. Add that to the fact that many immigrants don’t have a solid grasp on American politics and hold minimal cultural capital. Is it no surprise then that the children of immigrants go to college and become very liberal?

To illustrate my point, consider the perspective of this student-activist in a Boston Globe piece titled Young Asian Americans struggle to get immigrant parents to open up about a painful issue: racism. I don’t mean to single her out, as she is just one example of an experience playing out around many an immigrant family.

Rachel Wang had always been a bit critical of her Chinese immigrant parents. Their effusive gift-giving felt superficial. She found their inability to verbalize affection frustrating. Dinner was always a silent affair, until the end of the meal, when one of her parents would remind her there was still hot soup on the stove. It was an implicit expression of their love, but one evening, Wang snapped at them: “Why can’t you say something else to me?”

I’ve heard this criticism of so-called “Asian parenting” from many second-generation children: the idea that their parents are cold and thus must not care about them. This is, however, a reflection of different cultural modes of communication. Various cultures have various ways of showing affection, and there is often a clash when someone is raised by parents that subscribe to different cultural norms around communication of affection.

Like so many second-generation Asian Americans straddling two cultures, Wang struggled to communicate with her parents, and they struggled to communicate with her. But in a year marred by a deadly pandemic, social unrest, and surging anti-Asian violence, Wang and her parents have gotten closer by opening up about wounds from their pasts.

As Asian Americans reexamine their nebulous position in the country’s racial hierarchy, in which they are cast either as “model minorities” or “perpetual foreigners,” second-generation children such as Wang are breaking a long tradition of silence with their parents about subjects they never dared to broach before: race, racism, and identity.

I wonder why Asian immigrant parents are so silent about race? Maybe because race is one of the most complicated, contentious, and controversial issues in American discourse?

I’d say that race is the number one most controversial topic in America. Any discussion on race is bound to inflame tensions and spark visceral and emotional arguments. I spend an enormous amount of my time researching race and racial issues, and yet I know that I could spend every waking moment of the rest of my life reading about and debating race and still not manage to come even close to a complete perspective of race in America. No one can.

Yet she and the other students mentioned in the article expect their parents, who grew up in a monoracial society, to somehow understand an ever-evolving concept that is the most hotly contested and debated subject in both our historical and contemporary discourse.

“Asian Americans collectively are coming to a racial reckoning,” said Yoonsun Choi, a social work professor at the University of Chicago studying Asian-American families, “and in a way that the second generation is taking the lead of teaching the parents about the importance of ethnic solidarities and racial solidarities.”

For Wang, 21, these conversations with her parents started last summer, when she was marooned at their home in suburban New Jersey, biding her time until she could return to Brandeis University for her senior year. Following the killings of George Floyd and other Black Americans at the hands of police, Wang had thrown herself into the prison abolition movement and wanted to share what she’d learned with her parents. They were less receptive than she’d hoped.

Brandeis University is one of the highest-ranked colleges in the country. This means that the ideas that come out of there tend to be very theoretical and developed by people high up the ivory tower. No wonder her parents fail to grasp prison abolition. Almost no one can.

Prison abolition is an extremely niche ideology that has only gained some semblance of popularity over the past few years. Most Americans have never even heard of the prison abolition movement. No country has ever abolished prisons. And yet she expects her parents to magically understand a heavily theoretical ideology where its goals have never been tried in the entire world.

This means that she is in a massive bubble of her own. One in which all her peers support prison abolition and somehow expect everyone else to just “get it”. One that ignores the fact that an overwhelming majority of people want prisons to exist. But that’s just how deeply ensconced into the “college kid fed abstract theoretical ideas by ivory-tower intellectuals and is now ready to save the world via the power of holding up Instagrammable signs” bubble these activists are.

“At first, it was a [expletive] show,” she said, as their discussions devolved into heated arguments. “They came here to make money to create a stable household. They didn’t come here to be politically involved. In fact, if anything, they came here to escape political involvement.”

Many of Wang’s Asian-American friends were dealing with similar problems at home, and every night, they’d convene on a group chat to vent about the challenge of talking to their parents. And like her friends, Wang was angry. Surely, she’d figured, her parents, who had survived China’s violent Cultural Revolution, could empathize with systemic racism. So why didn’t they “get it,” she wondered? Why didn’t they understand?

This part would be hilarious if it wasn’t so sad. China’s Cultural Revolution was an authoritarian movement where bands of roving teens and young adults made public denunciations of anyone that dared to even slightly deviate from expected societal norms. Struggle sessions are the same concept as today’s cancel culture propagated by college-educated rabble-rousers that partake in witch-hunts over those they deem guilty of wrongthink. Just replace “traitor to Mao’s glorious Communist Party” with “traitor to the prevailing social justice doctrine”.

So when Wang acts incredulous that her parents magically don’t support the ramblings of a group of young political radicals that seek to punish dissenters and curb free speech, it shows a complete lack of understanding of what life was like under an authoritarian regime, and how similar her own newfound ideology pushes authoritarianism by calling it “social justice”.

The rest of the article goes on to detail other Asian American student-activists attempting to lecture their parents on hot-button political issues, to little avail. A pattern emerges:

Immigrants come to America for a better life, be it for economic or cultural or religious reasons. Some immigrants faced immense persecution in the countries they left. Many from former authoritarian regimes are appreciative of the freedoms in America’s Bill of Rights — free speech, due process, and religious freedom, to name a few — values that today’s progressives have left behind.

They often take jobs that are far less prestigious than the ones they had in the countries they left. They face massive language and cultural barriers that cut them off from mainstream society. Yet they work hard and try to make sure their kids will end up better off than they are.

Their children attend typical American schools that allow them to learn English and absorb mainstream American cultural and political norms. The kids often feel an internal tension between feeling American and feeling othered. Most kids just want to fit in, so they try to distance themselves from their “cringey” FOB immigrant parents. This complete rejection of their parents’ cultural values is especially prevalent for Asian kids because they are told early on (by Hollywood, their peers, etc.) that being Asian is uncool, and what kid wants to be uncool? Combine that with the lack of a cohesive alternative Asian American culture, and you get a lot of kids that are desperate to fit into whatever is popular at the moment.

Immigrant parents know that their situation is more precarious than native-born parents. They can’t let their kids “follow their dreams” of being a YouTuber or a pro football player. So they put more pressure on their children to aim higher in terms of education, where a degree from a good college is a near-guarantee of social mobility.

Their children often absorb the cultural and political views of their peers. There’s a strong sense that their parents and their parents’ views are “backwards” due to being from a different country.

The children go to college. The more elite the college, the more liberal the politics. Plus there is a far stronger pressure for these children of immigrants to assimilate into the mainstream, which on college campuses means adopting social justice ideology. Sometimes they overcompensate by trying to be as “in the know” as possible and turning into the ideas’ biggest proponents. Thus, being assimilated means supporting all the trendy social justice issues.

They come back to their parents and attempt to spread their newfound ideas to their parents. After all, it was their own parents that told them that elite colleges held the keys to success. So it follows that their parents should be accepting of the ideas taught at colleges these days.

This phenomenon is far from being just an Asian thing. Many a Latino immigrant parent have sent their child to an elite college only to end up scratching their head when their child returns and begins lecturing them on why “Latinx” is the “proper and inclusive” term. The same applies to African parents, parents from the Caribbean, Eastern European parents… the list goes on and on. The pattern is always the same.

And that is the irony of immigrant parents valorizing their children getting an elite college education. Soon enough, their children will come home from the colleges they told their children to get into, only to learn that the ideas their children are absorbing sound eerily like those of the countries they left behind.

The last paragraph is spot on. Assimilating into baizuo elite leftist culture turns Asians into boba court eunuchs. We have come full circle with the cultural revolution: https://yuribezmenov.substack.com/p/counter-the-cultural-revolution

Universities are drivers of what I call dolly-zoom diversity. A dolly zoom is what you get when a camera zooms out while moving towards an object, or zooms in while moving a way from an object; either way, the effect is to keep the object at the same size in the frame while altering the field of vision.

Dolly-zoom diversity likewise zooms in as it zooms out. It provides a platform on which drop-list differences (race, gender, sexuality, even language and religion) are raised up. But it ignores the fact that real difference is three-dimensional, that it involves different communities sinking different root systems into the soil, developing internal logics and priorities which by definition will not always jive with those of other communities. Instead, the university flattens these differences by teaching the same overarching framework of difference to members of all these communities, homogenizing their viewpoints in the very name of diversity. To the extent that universities sell their students a fool's-gold ticket while burdening them with a mountain of debt, they also homogenize these students' socioeconomic situations - this is especially true in the US, but it holds for many Canadians and Brits as well.

The usual counter to complaints about university "indoctrination" runs something like this: "Your kids aren't being indoctrinated. They're finally getting out into the world and meeting people from different backgrounds with different perspectives and leaving behind the two-bit dogmas you reared them on."

If this were the case, you'd expect university students to begin adopting a wide array of different and unexpected positions. Instead, the vast majority of them (certainly if they enter psychology and the humanities) come out with alarmingly uniform opinions. From what I've seen, many of these opinions are only vaguely held: one person may be vehemently in favour of prison abolition and pay dodgy lip service to the progressive line on gender issues, while for another it may be the other way around. This often speaks to people's masked, uneasy sense that they've adopted a particular set of stances less out of conviction than out of a socially-conditioned sense that these are the stances necessary to being a Halfway Decent Person who does the Bare Minimum.