No Affirmative Action for Asian Athletes

Sports should remain a meritocracy, as should all other fields in America.

There’s this rule in the NFL called the Rooney Rule. The Rooney Rule states that all NFL teams must interview and consider racial minorities for head coaching jobs. So when former New England Patriots tackle Eugene Chung was interviewing for a coaching job, he thought that he could get an affirmative action boost due to being a racial minority.

But that’s not what happened.

When Chung brought up his race, the interviewer told him that he was “not the right minority that we’re looking for”. Chung lamented this statement, saying that “It's just when the Asians don't fit the narrative, that's where my stomach churns a little bit. For me, in this profession, I don't think I'm looked at as a minority.”

In reality, Asians are the ultimate minority in his profession. There are 1,696 current NFL players. Only one current player in the entire NFL, Atlanta Falcons kicker Younghoe Koo, has two biological Asian parents. A few other players are of mixed Asian descent, like Los Angeles Rams safety Taylor Rapp and Arizona Cardinals quarterback Kyler Murray.

The National Football League’s acronym is often joked to have another meaning: Not For Long. Indeed, the NFL is Not For Long. Turns out it is also Not For Chung, Not For Xu, Not For Nguyen, Not For Kim, Not For Patel, and Not For Singh. Asians are almost nowhere to be found in the nation’s most popular game.

This is true of all major American sports. Asians are also near-invisible in the NBA and the NHL. The MLB is the only league out of the Big 4 to have a statistically significant number of Asian players: 2%, which is still way less than the proportion of Asian Americans as a whole. Not to mention that most Asian MLB players are imported from Japan and South Korea, including, of course, two-way superstar Shohei Ohtani.

The lack of Asians in American sports has profound implications for how Asian Americans are viewed in this country. In a heavily politically polarized America, sports are one of the few areas where Americans of all races can sit back and cheer for people based on team instead of by political affiliation or race. The lack of Asian players essentially locks Asians out of being seen as real Americans—a perception that Asian Americans have been trying to eradicate for centuries. The dearth of Asian players also makes Asians seem weak and unathletic—another stereotype that we’ve been challenging for a long time.

Yet despite all this, I do not want affirmative action for Asian American athletes. I do not want Asian players to get into sports leagues with lower standards. I do not want affirmative action to exist for any race in any field.

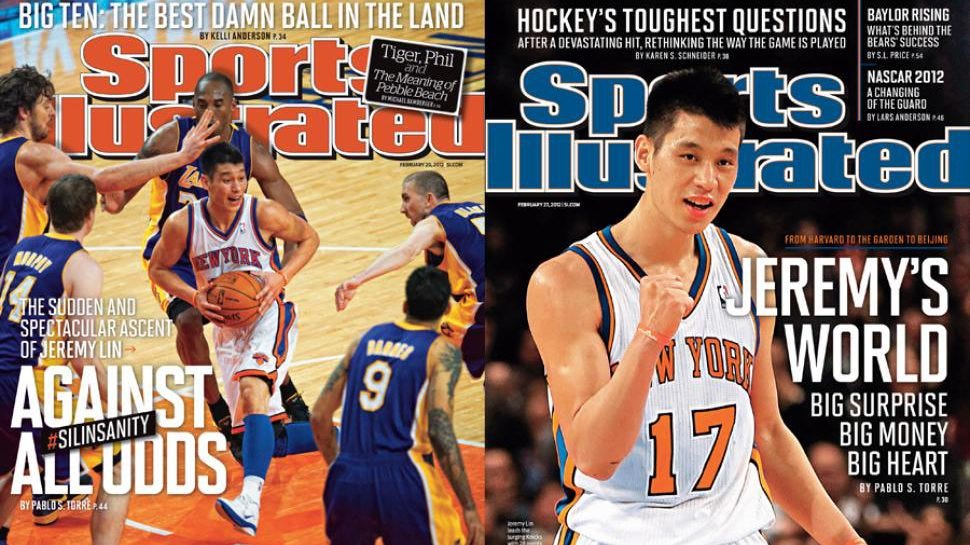

There was a time back in 2012 when the world experienced “Linsanity”, where NBA player Jeremy Lin went from a complete unknown into a global sensation. Those days now seem like a fever dream to me. For the first time in as long as I could ever remember, the entire nation seemed to be talking about an Asian American person. Sports Illustrated put him on back-to-back covers. The first cover expressed what we all knew: Lin had made it into sports royalty against all odds.

What made Lin’s successes all the more sweeter was that we knew Lin was not helped by affirmative action. In fact, Lin had received the opposite of affirmative action. Even though he played well in high school and college, scouts would pass him over, presumably because they didn’t think an Asian player would be good, despite the stats showing otherwise. During Lin’s college days, hecklers would taunt him with shouts of “Wonton soup” and pseudo-Chinese gibberish talk. Lin’s meteoric rise was an underdog sports movie come to life: an epic tale of a player that defied racism and everyone doubting him to become the star of the show.

Imagine, then, if affirmative action had been instituted in the NBA before Lin’s rise. Subpar Asian American players would have played in the big leagues. And on the court, it’s very noticeable when a player just isn’t good enough. Had subpar Asians been allowed to play via affirmative action policies, they wouldn’t have done as well. And if they didn’t do well, which is likely to happen for affirmative action players, then people would assume that all Asian players were bad. Perhaps Lin then never would’ve had a chance to play at all. Linsanity might have never happened.

The other big thing is, well, sports fans don’t want affirmative action. Despite the fact that all the sports leagues besides the MLB fail to come close to replicating the racial composition of America, there has been no real big movement to push for racial balance in sports. Sure, there might be articles whining about the lack of Black representation in hockey, but since when did most Black Americans even want to play hockey?

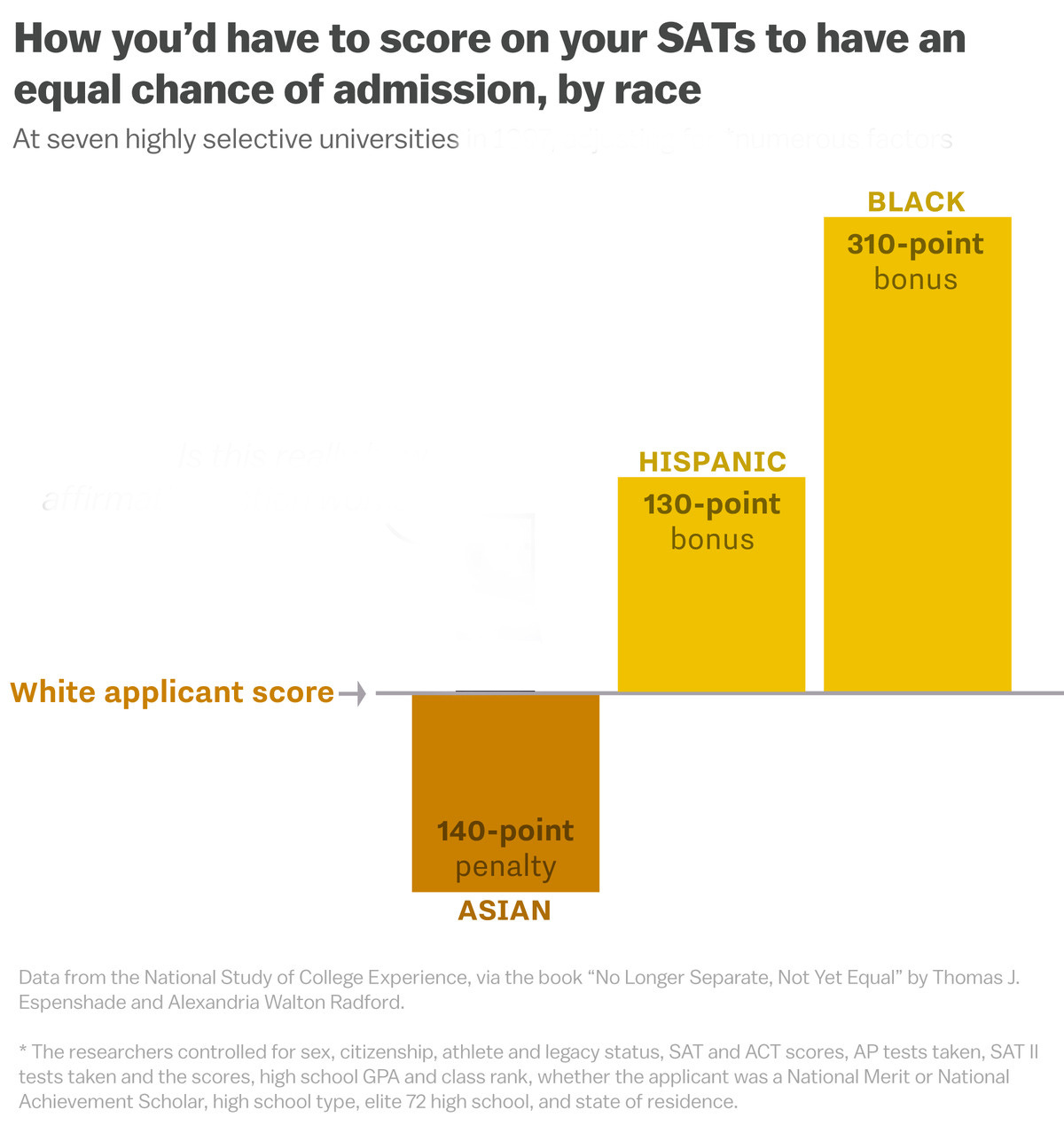

The obvious parallel to sports here is affirmative action in academia. Colleges admit Black and Latino students with lower standards than Asian and White students.

Many Black and Latino students have complained that other students believe that they only got in because of affirmative action. This problem can easily be solved by abandoning all affirmative action policies. When I was at Stuyvesant High School, the most selective high school in New York City, no one ever thought that the Black and Latino students there got in because of affirmative action. We all knew that the only way of getting in was scoring high enough on a standardized test.

Yet elite public high schools have increasingly been overtaken by the DEI regime and are being pressured to abandon standardized testing. Top high schools across the country, from San Francisco’s Lowell High School to Virginia’s Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology, are increasingly abandoning merit and developing lottery-based admissions policies. The results have been overwhelmingly negative. The first year Lowell switched from a merit system to a lottery system, racial diversity went up—and the number of failing grades skyrocketed.

This isn’t just limited to high schools. As affirmative action scholars Richard Sander and Stuart Taylor Jr. have found,

[E]ven though blacks are more likely to enter college than are whites with similar backgrounds, they will usually get much lower grades, rank toward the bottom of the class, and far more often drop out. Because of mismatch, racial-preference policies often stigmatize minorities, reinforce pernicious stereotypes, and undermine the self-confidence of beneficiaries, rather than creating the diverse racial utopias so often advertised in college-campus brochures.”

Not to mention that affirmative action has devalued the achievements of the students that could get in without it. There are perhaps few worse feelings than working hard and achieving something big only to have everyone else think you didn’t have to work for it. That wasn’t the case with Jeremy Lin, and that was what made his successes so much more larger-than-life, and a big reason why his underdog story really inspired many. There’s no underdog movie about someone who manages to succeed because other people tipped the scale in their favor.

Ibram X. Kendi, the High Priest of Antiracism, once proclaimed, “When I see racial disparities, I see racism.” There are large racial disparities in the participation rates of Asian Americans in professional sports. So when will Kendi speak up about anti-Asian racism in the NBA, NFL, and NHL? (Or anti-White racism in the NBA and NFL, and anti-Latino racism everywhere besides the MLB)

Perhaps Kendi thinks, as Eugene Chung and all the high-achieving Asian kids being rejected from college have learned, that Asians just aren’t the right minority.

I’ve recently started using Twitter, follow me for more political and cultural commentary.

People who support affirmative action in other areas are often very opposed to it in sports. It’s an odd contradiction that I wish more people would think about. Because I think the reason is that people see sports as something where ability really matters, which means that they see college (or diversity hiring in business) as something where ability does not matter. And that’s a very strange way to look at college. Does that mean that most people see college as nothing more than a symbolic achievement? Where the achievement is getting accepted, not graduating? It’s like they don’t see college as a competitive learning environment. Same for diversity hiring in private industry or government positions as well.

I very much agree with your take.

Often absent from these conversations are matters of cultural preferences, which I think maybe we’re not supposed to talk about anymore...? In the same way that black Americans are overrepresented in athletics, Asian Americans are overrepresented in a field I hold dear, the symphony orchestra. From this I merely conclude that the parents of children in these respective groups have different ideas about what works for their kids. This is sort of a similar argument to the one about why men are more often engineers than women, I suppose.

I would be curious to know the participation rates in youth sports among Asian American kids. And I’d be equally curious to know the participation rates in youth orchestras among black American kids.